How to Make the Most of Your Holidays

Arav Khanna

Introduction

The concept of "wave-particle duality" in physics is a fascinating one - as a result of several important experiments carried out during the 20th century, physicists found that light had both the properties of waves, as well as the properties of particles, a contradiction to all previous understandings of physics, where something could be only a wave or a particle. This wonderful fact, with all of its immeasurable consequences for quantum mechanics and our understanding of the universe, meant nothing to me as a high school student, though I could recite it to you word-for-word had you asked me.

The only weight that this fact held for me was that it was part of an important exam I had coming up, which, in hindsight, is extremely unfortunate. Abstract, thought-provoking concepts in physics, and any other subject for that matter, are gifts; gifts that should be appreciated, experimented with, and pondered over. At the time, however, all that mattered was getting into university.

I'm not in any position to say whether it's right or wrong, but regardless, the fact remains: The education system is not designed to give you your sweet time to learn and appreciate something new. For many in university, assignments are released as early as the first day of the term. High school, though less intensive, still warrants regular exams and take-home assessments. In spite of these time challenges, studying is doable, but learning, that is, taking the time to deeply ponder, experiment with, and apply course material - can be extremely difficult during the term.

The term break is a fantastic time to be able to learn slowly and at a deeper level, when assessments aren't breathing down your neck. In this article, I'll be breaking down a systematic process for you to use to study effectively during your break, regardless of what subjects you're taking.

#1: Proving leads to Understanding

.jpg)

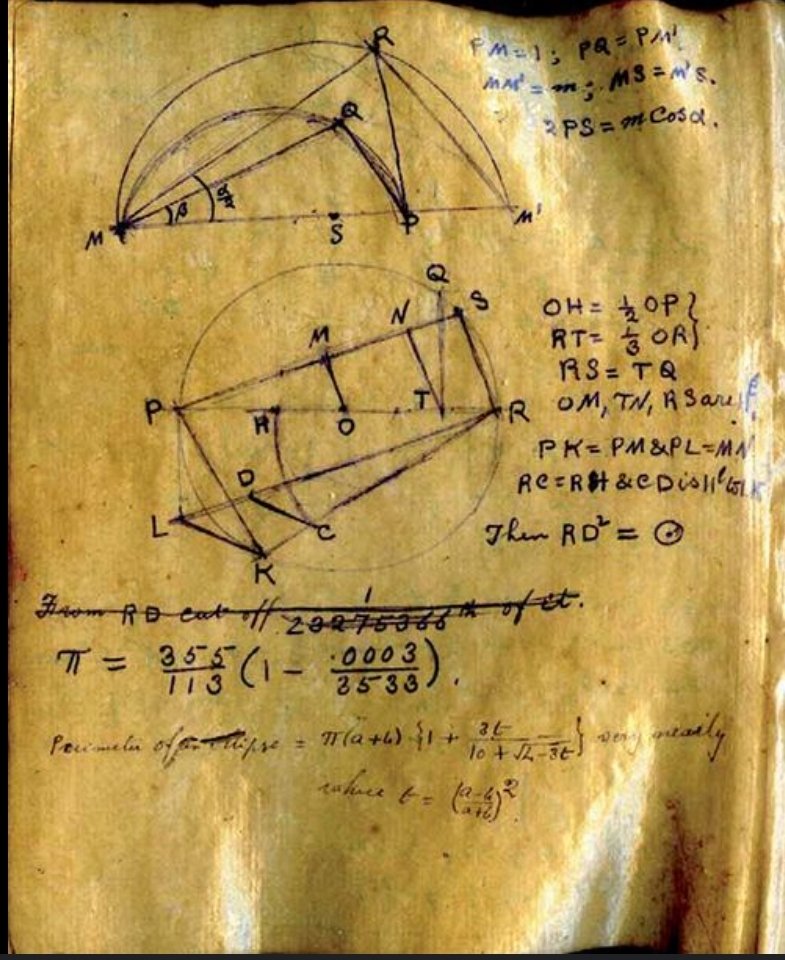

Srinivasa Ramanujan is widely regarded as one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, and to the people around him, he had been nothing short of a magician. His ability to produce complicated formulas and theorems had confused even the most accomplished mathematicians of his time.

What wasn't known, however, was that Ramanujan's seemingly magical abilities were born of countless hours spent proving and discovering his own results. Ramanujan lived in extremely poor conditions while in India, limiting his access to mathematics resources. One of the few books that he owned during his early development had been 'A Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure and Applied Mathematics' by George Shoobridge Carr, a book that presents its results in a concise manner with little explanation or proofs. He'd taken it upon himself to produce his own proofs and explanations for the results in the book, essentially learning by working backwards.

In school, we're taught to do the opposite - to accept facts for what they are, and to continue to use them in problems. However, this doesn't help us understand why the fact is true, or how it's related to other facts - but we force ourselves to ignore these questions in the interest of the little time that we have. That being said, your holidays are a perfect time to challenge and critique your upcoming course material. If you read that a mathematical formula is true, don't just accept it - try to prove it yourself, or at least understand why it must be true. If you're learning about a historical event, don't just memorize the date - try to understand the web of causes and effects that led up to it, and how they justify the event (even if it isn't part of your syllabus). This deeper level of engagement with your course material will not only help you understand it better, but will also make it more enjoyable and memorable.

I've been using this technique relentlessly for the past year or so during my term breaks, in preparing for difficult university-level courses in mathematics and physics. As ridiculously beneficial as it is, it can be extremely difficult to take a fact and work backwards, and I occasionally find myself really struggling to do so. This leads me to my next point:

#2: Master a subject by struggling with it.

In one instance during 11th grade, I'd received the second-highest mark in my cohort for a biology final exam. While this may have been exciting in any other scenario, I'd been extremely disappointed. I'd gone to great measures to ensure that nobody could've possibly beaten me - studying all of the course content during the holidays before the term had even started, doing several practice exams, reviewing the material several times, and yet, I'd come second. It was a harrowing experience that made me become seriously insecure about my intelligence - if I'd done more preparation than anybody else, and still failed in ranking first, something must have been wrong with me.

What I'd failed to understand was that, in the case of learning, quality is significantly more important than quantity. I'd been measuring my mastery of biology based on how many hours I'd studied the content, or how many textbook chapters I'd studied ahead of time, and not based on the actual quality of that time spent - which was, for all intentions and purposes, extremely poor. After having a conversation with the student who'd come first, I'd realized this was a fundamentally flawed way to approach learning - I may have spent significantly more time "studying" than they did, but they had struggled more than I had, and that was what set us apart.

We all understand that top students get good grades by thinking about concepts "deeply". But what does that even mean? What does the process of "thinking about a concept deeply" actually look like?

What it means to "think deeply", I would learn, is struggle and failure. When we struggle with a concept, or a problem, we're forced to address and repair our own gaps in understanding. This struggle creates deeper neural pathways and more lasting comprehension than simply writing notes, looking at answers, or memorizing. The process of wrestling with difficult ideas, making mistakes, and gradually working towards understanding is what separates surface-level knowledge from true mastery. After my conversation with my aforementioned peer, this is what I'd realized - I may have spent significantly more time "studying" than they did, but they had struggled more than I had, and that was what set us apart.

But we don't have infinite time. How much struggle is too much?

There is definitely a point during the struggling process at which the benefits begin to decrease - identifying that point is an extremely critical component of time management as a top student. In his book Ultralearning, Scott Young introduces his concept of a "struggle timer" - When you feel that you've reached a point where you've tried everything, where you couldn't possibly think of any new ideas, try giving yourself an additional 10-15 minutes to really try and think out-of-the-box in regards to the problem you're trying to solve, or the concept that you're trying to understand. Re-consult the resources available to you, and see if you can look at the problem/concept from a different angle.

Personally, I've adapted this method based on the complexity of the problem or concept I'm dealing with. If I'm training my basics in mathematics, as I often do, and struggling on a problem, I'll give myself a "struggle timer" of 10-15 minutes. If it's a more complex problem, such as a detailed proof from a pure mathematics course, I'll give myself 25-30 minutes.

What do I do if I've given myself a "struggle timer", and still can't come up with a solution?

This point is an excellent time to consult the solution. After taking time to struggle with a concept, looking at its solution can be extremely beneficial - you've already engaged with the problem deeply, and have a better understanding of where your gaps in knowledge are. This makes the solution significantly more meaningful, and memorable, than if you'd looked at it right away. Additionally, you can compare your thought process to the solution's approach, and identify where you went wrong or what you missed.

#3: External experimentation

With a rapidly increasing global population, and by extension, increasing numbers of students and professionals competing for the same grades, universities, or internships, it has never been more important to learn in a way that distinguishes you from the rest of your competition. One way to differentiate yourself is through external experimentation - taking what you learn in class and applying it to real-world scenarios or personal projects. Though this is fairly common knowledge, many students are so swamped with assessments that they simply don't have time to commit to an innovative personal project - this is why the holidays are a perfect opportunity to do this.

Making an effective project

Personally, I follow one simple rule when I embark on a quest to apply my classroom knowledge in an unfamiliar scenario: Don't do what everybody else does.

Out-of-the-box thinking is hard, and so, many people within a given field of study will likely produce the same projects or experiments over and over again. For instance, a common project among computer science students would be a to-do list app. In the humanities, many students might write essays analysing common literary works that have been discussed countless times before. While these projects are great stepping stones to a more complex project, and demonstrate technical competency, they don't necessarily showcase creativity or innovative thinking. The key is to find unique applications or combinations of your knowledge that a limited amount of people have explored before.

Of course, to simply say "do something that hasn't been done before" is extremely hand-wavy advice. The reason why the particular project hasn't been made before is because it would require a great deal of creative and innovative thinking - but this ties right back to our struggle principle. In an ocean of candidates, universities and hiring managers are looking for individuals who are willing to stretch themselves to solve problems that have never been solved before, or even to recognize such problems to begin with.

A peer of mine studying Computer Science and Financial Mathematics, after having worked through several smaller projects, spent a significant amount of time on an app that provides users with unique, in-depth insights into their investment portfolio. He's since presented the project at the university, and gone on to receive a series of software engineering jobs at different companies. Personally, I often spend my holidays working through mathematics problems not even required of my coursework, allowing my curiosity to take over and looking through higher-level textbooks, Olympiad problems, and unsolved proofs. It's thanks to to these curiosity-driven initiatives that I have a strong, unique intuition for my primary coursework.

Conclusion

Overall, the holidays are a great time to be creative with the information you've learnt in class, in a way that you couldn't do before.